This week's

blog comes from the pleasant confines of MoMo's café, just off the Hongfu Road

in Central Dongguan. The café has only opened in recent weeks and still has a

range of teething problems; the lack of electricity to the points being the

most obvious. Still, one word and I had five different people running around

trying to sort out the problem. Duly solved, I can now sit back amongst the

minimal chic décor (actually, an odd mixture of minimal and New York of the

1990's) and enjoy a very reasonable

Americano together with a complimentary tea, a special offer for this opening

month apparently. MoMo, who runs the joint and cooks a range of Western style

snack dishes for her clientèle, buzzes around the table, ever wanting to

practice her English or to indulge her apparently insatiably sociable nature.

New Year came

and went, although it never did quite completely go as the festivities seem to

go on for far, far longer than in other cultures. The event itself triggers a

mass migration from the larger, first and second tier cities back to the

smaller towns and villages. Such holidays in China I now assume to be the very worst

time to travel as one is almost guaranteed incredibly long queues, huge and

crushing crowds, and tiresomely draining delays into the bargain. I experienced

one such festival earlier this year when I was unwise enough to travel to

Guilin in the week before 'Tomb Sweeping Day'… never again!

This New

Year's mass migration was further complicated by the visitation on South China

of record low temperatures. Dongguan itself even had snow on the day I arrived

– an event that brought out crowds of people to take snaps of this strange

phenomenon. The local hub, Guangzhou, a city with a population over 14,000,000,

suffered something of a crisis when 100,000 people were attempting to catch

non-existent trains (cancelled due to the bad weather) and cramming themselves

into an already over-crowded railway terminus. The people who heard about this

on the news reacted in a fairly typical way for China and decided to head for

the station even earlier, thus exacerbating the already dire over-crowding.

To be fair,

the Chinese Authorities actually reacted to this situation fairly well, firstly

by keeping social order (although apparently the crowd was remarkably good

natured in the circumstances), and secondly by laying on extra high-speed

trains at no extra cost, which enabled many of the travellers to be reunited

with their families somewhat earlier than they had originally planned.

Family, it

seems almost superfluous to point out, is extremely important in Chinese

culture. So much so that people are willing to undergo the huge challenges of

travelling at this time of year, 13 to 14 hour train journeys, hustle, bustle,

overcrowding and almost endless aggravation in order to be received in the

presumed warm bosom of their families. Understanding the importance of family

here is fundamental to understanding Chinese culture itself. It is the one

abiding notion that trumps all else in Chinese values. If you are in with the

family, you are well in – you are welcome and treated royally. For those

outside the group though, it is a profoundly different matter. In many ways

this society is perhaps the very last in the world that should have pretended

to be communist. The leaders here are fond of a phrase to describe the system

of government: 'Communism with Chinese characteristics'. What this effectively

means is something that is so alien to any notion of communism that would be

intellectual recognisable as being such as to bear no relationship whatsoever.

Instead, the critical factor is is family and, by extension, family connections.

I have

struggled over many visits to pin some kind of label, some kind of name for the

system here in China. Communism it is not, self-evidently so, but it is not

really capitalism either, although capitalism comes far more naturally to the

Chinese than perhaps any other system. The influence of Confuscius, for good

and for ill, echoes down the years and is still critical to Chinese thinking to

this day. However one labels the system, one has to admit that, for all its

drawbacks and weaknesses, it works. Sometimes, it more than just works, it is a

positively dynamic force for growth and change (at least in the economic sense

– the environment is, of course, quite another matter).

I was

fortunate enough to enjoy New Year's Night (Feb 7th) with a family

of a friend in Dongguan. The event was celebrated much like Christmas is in the

West: an excess of food is consumed, too much alcohol drunk, too much spent on

gifts of nebulous benefit to the recipient. Added to the more modern, at least

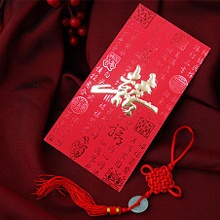

for the Chinese, notion of giving gifts at this time, there is also the

obligation to provide contributions to the nearest and dearest through the

'Hongbao' system. 'Hongbao' quite literally means 'red envelope', which will in

practice contain a sum of money and is given by certain members of the family

and friends to others within the group. Generally, the sums involved are

between ten (£1/$1.50) and hundreds, or sometimes even thousands of yuan (the

more well-off Chinese often love the opportunity to ostentatiously display both

their wealth and their generosity).

The vast

majority of families like to stay at home together rather than going to

external, organised events. And the vast majority of such families will spend

most of the evening, from 8pm to 12pm, watching the state sponsored TV special.

Most of this extravaganza would not have been out of place 30 odd years ago in

the West. It consists of comedic skits, songs, often of a patriotic nature, and

large scale dance performances. It is all quite impressive, but feels somehow

dated, harking back to an era of entertainment that has long passed in the

West. Added to this however, there was also a disquietingly large amount of

time given over to watching soldiers stamping their feet in unison and

generally behaving as those in the military seem to love to do, ie shouting at

each other in a very loud voice and acting like automatons. Patriotic songs

followed this section. Maybe it is just me, but I always find such displays of

mindless nationalism chillingly reminiscent of less pleasant aspects of Europe in the 1930's.

Oddly,

although there were many, many fireworks that simply went 'bang', often being

so numerous as to create a ripple effective, there were strangely few colourful

displays. Again I found this surprising for China, the very land where both

gunpowder and fireworks were first brought into being. The actual stroke of

midnight was something of a damp squib, rather than a pyrotechnic extravaganza;

the odd bang here and there with no apparent co-ordination or order.

The next

day's celebrations in Qi Feng Park were more impressive – although the

fireworks were limited once again to the banging varieties, there were huge

amounts of them at the Buddhist temple there. This was combined with the

burning of huge amounts of incense with lent the air a very pleasant, if

somewhat pungent, atmosphere and enveloped everything in a very fragrant smoke.

Back in the

café, I find myself enjoying my first chance to relax and write for three days.

The week-end and the days following were somewhat packed with visits and

events, so much so that I find myself relishing this short gap of 'free time'

here in the café. It seems that there will be more celebrations to come in the

next week so, for now, time to gird one's loin, stay calm and carry on regardless…

No comments:

Post a Comment