"Leisure is the Mother of

Philosophy".

|Thomas Hobbes

This week’s blog is brought to you from perhaps my favourite port of call of the moment, the Hey!!! Cyber Cafe just off the main square in South Dongguan. The coffee is reasonable and reasonably priced, a comparative rarity for China. The décor is wonderfully minimalist and the staff are friendly and helpful. The only downsides are the constant muzak, in this case an icky pop/rock selection of current Chinese favourites, hence particularly tiresome, and the fact that despite many signs to the contrary a host of customers who insist on smoking. This is perfectly normal in China where such rules are routinely ignored if inconvenient, much like zebra crossings, traffic lights and theoretically pedestrianized zones. There is the world of difference here between what is supposed to happen and what actually happens.

Throughout my life I have felt myself to be something of a rebel, someone who finds it not only convenient to ignore certain rules but actually has great difficulty understanding their significance in the first place. This has been both a blessing and a curse. A blessing in the sense that I have been happily free from the pressures that many feel to conform to some arbitrary norm, but a curse in that I sometimes inadvertently break some social convention or rule, much to the annoyance of people I value as friends. Given this, I find myself somewhat divided in my feelings about the attitude of so many Chinese citizens, and their ubiquitous and routine flouting of rules and conventions. In some ways I find it really quite annoying, as with the smokers right now, in others there is something actually quite liberating about their refusing to do something just because someone, somewhere has made up a rule about it.

In this particular discussion I take no position, have no guidelines and admit myself quite bereft of recommendations, let alone answers, but during my travels these thoughts have often occupied my mind. I ponder this question often, it goes to the heart of the nature of governance and even the need for governance at all.

I must admit to finding myself confounded and confused, befuddled and bemused as to whether the imposition of strong governance is a good thing in that it imposes an amount of ‘civilized’ behaviour and standards on the citizens governed, or a bad thing in that it limits, sometimes to a quite extraordinary extent, liberty and expression.

It seems I am not alone in my discombobulation, this question has vexed many a philosopher since the beginnings of what passes as civilization. The great 17th century English thinker Thomas Hobbes stated: “During the time men live without a common power to keep them all in awe, they are in that conditions called war; and such a war, as if of every man, against every man.”

His fear was, that without the control of law and governance, man would revert to a condition of internecine and ongoing war, each person, family, tribe and group struggling with and against each other. Given the ongoing state of the World over the centuries since he wrote those lines, it is difficult to disagree with him.

A couple of millennia previously, the Greek dramatist Sophocles had put it perhaps even more simply: “There is no greater evil than anarchy.”

The country I find myself in at the moment, the People’s Republic of China, brings these questions sharply into focus. There is an odd admixture here between very strict laws in any area in which the government feels the possibility of a threat to its authority, the ban on any meaningful protest and the constant, paranoid monitoring of every action on the internet being obvious examples, combined with a completely laissez-faire approach to law enforcement in general. The smoking ban in cafés is an obvious example of laws that have been passed but remain completely unenforced. The roads here are perhaps the most anarchic I have ever seen in a theoretically civilized country, drivers tending to do whatever happens to enter their heads at any given moment without the slightest consideration of others around them or concern about rules, laws or regulations.

As sino-advocates never tire of reminding us, Chinese civilization goes back some five thousand years or more, but the results of this ‘civilization’ are hard to see in the day to day behaviours of people here, particularly when they are in a position of power or behind the wheel of a car.

An opposing view to Hobbes was put forward by the much-admired American writer Henry David Thoreau who advocated the freeing of people from the constraints of government when he said: “That government is best which governs least. The best government governs not at all"

He has a point, and one that is supported by many in America who consider themselves libertarians in the sense that they feel their freedoms should be protected from interference from government. In their view, the US government should be as small as possible or even, ideally, non-existent. For my part though, I must admit to a certain alarm at the thought of a complete lack of governance. It would seem clear that Thomas Hobbes had a valid point in relation to the probable result of complete freedom.

So, given that we need to have some form of governance for civilization to exist at all and for us not to live in constant fear of anarchy and/or violence from our fellow man, the question becomes what form of government should we have and how is it to gain legitimacy in the eyes of the populace.

I quoted Tony Benn on this issue last week, but perhaps this would be an appropriate occasion to give the full text as it makes several interesting and valid points: “In the course of my life I have developed five little democratic questions. If one meets a powerful person--Adolf Hitler, Joe Stalin or Bill Gates--ask them five questions: “What power have you got? Where did you get it from? In whose interests do you exercise it? To whom are you accountable? And how can we get rid of you?” If you cannot get rid of the people who govern you, you do not live in a democratic system.”

Such thoughts often occur to me when faced with living in the quixotic and paradoxical China or holidaying in the semi-anarchic corruption of Thailand. Just where do such governments gain their legitimacy? And how is this legitimacy ever tested? Authority is often enforced through the arms of the state such as the police or the military, but is this, as W.W.W. McNally once pointed out, simply a case of the police being the biggest gang in town with access to the most resources?

Such questions leave me vexed and perplexed on a regular basis. In all humility, I have to admit to having no answer but merely the desire to fathom the depths of these conundrums, to attempt to arrive at some kind of valid position, if not a solution.

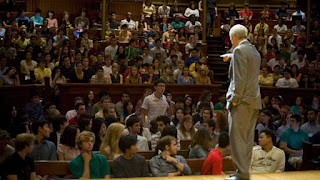

For anyone interested in such arcane but fascinating debates I would recommend checking out the Harvard lectures of the excellent Michael Sandel. He has the habit of asking the most obvious of questions and demonstrating again and again that the answers themselves are nowhere near as obvious as the questions.

Back in the Hey!!! Cyber I take another sip of their reasonable Americano and look around at my fellow customers. In some ways at least, I have to admit to finding them pleasingly pragmatic. Over the past 150 years or so the Chinese have seen many systems of governance come and go, from Emperors to Democrats, from Fascists to Communists, to arrive at the present ambiguity whereby those in power pay lip service to communism, or at least to ‘the Party’, but in reality follow policies that are in themselves simply pragmatic in nature. Perhaps China is the first country to arrive at a solution to the endless political debates that have divided men seemingly forever. They seem to have reached a point that perhaps can be best described as post-politics, or at least post-idealism. Sadly for those of us who still have some vestige of belief in political ideals, perhaps that is the best that the human race, with all its greed, its violence and its irrationality, is actually capable of?

|Thomas Hobbes

This week’s blog is brought to you from perhaps my favourite port of call of the moment, the Hey!!! Cyber Cafe just off the main square in South Dongguan. The coffee is reasonable and reasonably priced, a comparative rarity for China. The décor is wonderfully minimalist and the staff are friendly and helpful. The only downsides are the constant muzak, in this case an icky pop/rock selection of current Chinese favourites, hence particularly tiresome, and the fact that despite many signs to the contrary a host of customers who insist on smoking. This is perfectly normal in China where such rules are routinely ignored if inconvenient, much like zebra crossings, traffic lights and theoretically pedestrianized zones. There is the world of difference here between what is supposed to happen and what actually happens.

Throughout my life I have felt myself to be something of a rebel, someone who finds it not only convenient to ignore certain rules but actually has great difficulty understanding their significance in the first place. This has been both a blessing and a curse. A blessing in the sense that I have been happily free from the pressures that many feel to conform to some arbitrary norm, but a curse in that I sometimes inadvertently break some social convention or rule, much to the annoyance of people I value as friends. Given this, I find myself somewhat divided in my feelings about the attitude of so many Chinese citizens, and their ubiquitous and routine flouting of rules and conventions. In some ways I find it really quite annoying, as with the smokers right now, in others there is something actually quite liberating about their refusing to do something just because someone, somewhere has made up a rule about it.

In this particular discussion I take no position, have no guidelines and admit myself quite bereft of recommendations, let alone answers, but during my travels these thoughts have often occupied my mind. I ponder this question often, it goes to the heart of the nature of governance and even the need for governance at all.

I must admit to finding myself confounded and confused, befuddled and bemused as to whether the imposition of strong governance is a good thing in that it imposes an amount of ‘civilized’ behaviour and standards on the citizens governed, or a bad thing in that it limits, sometimes to a quite extraordinary extent, liberty and expression.

It seems I am not alone in my discombobulation, this question has vexed many a philosopher since the beginnings of what passes as civilization. The great 17th century English thinker Thomas Hobbes stated: “During the time men live without a common power to keep them all in awe, they are in that conditions called war; and such a war, as if of every man, against every man.”

His fear was, that without the control of law and governance, man would revert to a condition of internecine and ongoing war, each person, family, tribe and group struggling with and against each other. Given the ongoing state of the World over the centuries since he wrote those lines, it is difficult to disagree with him.

A couple of millennia previously, the Greek dramatist Sophocles had put it perhaps even more simply: “There is no greater evil than anarchy.”

The country I find myself in at the moment, the People’s Republic of China, brings these questions sharply into focus. There is an odd admixture here between very strict laws in any area in which the government feels the possibility of a threat to its authority, the ban on any meaningful protest and the constant, paranoid monitoring of every action on the internet being obvious examples, combined with a completely laissez-faire approach to law enforcement in general. The smoking ban in cafés is an obvious example of laws that have been passed but remain completely unenforced. The roads here are perhaps the most anarchic I have ever seen in a theoretically civilized country, drivers tending to do whatever happens to enter their heads at any given moment without the slightest consideration of others around them or concern about rules, laws or regulations.

As sino-advocates never tire of reminding us, Chinese civilization goes back some five thousand years or more, but the results of this ‘civilization’ are hard to see in the day to day behaviours of people here, particularly when they are in a position of power or behind the wheel of a car.

An opposing view to Hobbes was put forward by the much-admired American writer Henry David Thoreau who advocated the freeing of people from the constraints of government when he said: “That government is best which governs least. The best government governs not at all"

He has a point, and one that is supported by many in America who consider themselves libertarians in the sense that they feel their freedoms should be protected from interference from government. In their view, the US government should be as small as possible or even, ideally, non-existent. For my part though, I must admit to a certain alarm at the thought of a complete lack of governance. It would seem clear that Thomas Hobbes had a valid point in relation to the probable result of complete freedom.

So, given that we need to have some form of governance for civilization to exist at all and for us not to live in constant fear of anarchy and/or violence from our fellow man, the question becomes what form of government should we have and how is it to gain legitimacy in the eyes of the populace.

I quoted Tony Benn on this issue last week, but perhaps this would be an appropriate occasion to give the full text as it makes several interesting and valid points: “In the course of my life I have developed five little democratic questions. If one meets a powerful person--Adolf Hitler, Joe Stalin or Bill Gates--ask them five questions: “What power have you got? Where did you get it from? In whose interests do you exercise it? To whom are you accountable? And how can we get rid of you?” If you cannot get rid of the people who govern you, you do not live in a democratic system.”

Such thoughts often occur to me when faced with living in the quixotic and paradoxical China or holidaying in the semi-anarchic corruption of Thailand. Just where do such governments gain their legitimacy? And how is this legitimacy ever tested? Authority is often enforced through the arms of the state such as the police or the military, but is this, as W.W.W. McNally once pointed out, simply a case of the police being the biggest gang in town with access to the most resources?

Such questions leave me vexed and perplexed on a regular basis. In all humility, I have to admit to having no answer but merely the desire to fathom the depths of these conundrums, to attempt to arrive at some kind of valid position, if not a solution.

For anyone interested in such arcane but fascinating debates I would recommend checking out the Harvard lectures of the excellent Michael Sandel. He has the habit of asking the most obvious of questions and demonstrating again and again that the answers themselves are nowhere near as obvious as the questions.

Back in the Hey!!! Cyber I take another sip of their reasonable Americano and look around at my fellow customers. In some ways at least, I have to admit to finding them pleasingly pragmatic. Over the past 150 years or so the Chinese have seen many systems of governance come and go, from Emperors to Democrats, from Fascists to Communists, to arrive at the present ambiguity whereby those in power pay lip service to communism, or at least to ‘the Party’, but in reality follow policies that are in themselves simply pragmatic in nature. Perhaps China is the first country to arrive at a solution to the endless political debates that have divided men seemingly forever. They seem to have reached a point that perhaps can be best described as post-politics, or at least post-idealism. Sadly for those of us who still have some vestige of belief in political ideals, perhaps that is the best that the human race, with all its greed, its violence and its irrationality, is actually capable of?

No comments:

Post a Comment