Today my flaneurial duties

find me gently lapping at a bowl of 'dou nai', which roughly translates to,

warm soya milk (with a little added sugar). It is a great favourite in these

parts and is often given away free with meals. In this particular café, they

charge the exorbitant sum of 1 Yuan (10p or 16 cents) if you take some with

your morning meal. I hesitate to say breakfast as it is already 10.30 in the

morning; another late night due to the

demands of my friend's addiction to tai chi, demands which sometimes mean that

I get dragged into taking exercises of various sorts very late in the evening.

My friend is a great devotee of Tai Chi itself whereas I

only tend to indulge in some of the more esoteric offshoots such as 'Qigong'

(energy work) and 'Pai Da' , a form of exercise therapy that involves slapping

various strategic points on the body. The latter I find particularly enjoyable

although it does tend to border on the masochistic at times. In the version we

practice, one slaps five different locations; the inside of the elbows, the

armpits, the groin (carefully!), the backs of the knees and the insteps of the

feet. When I say slap, I don't mean a gentle tap but a full-blooded, vigourous

slap, the effect of which feels as if the skin is being stung, hard and

continuously. This is repeated a large number of times until the blood raises

to the surface and the area thus treated has turned quite red. At least, that

is the hoped for result. Other colours, in theory at least, indicate an

imbalance in the body's energy that will necessitate drawing out with yet more

slapping. The exact imbalance is indicated by the precise colour that comes to

the surface of the skin.

Many of these practices, like Tai Chi itself, go back

centuries and are deeply rooted in the Chinese psyche. One sees them everywhere

in the squares and parks of Chinese cities, sometimes even 'en masse' as

hundreds of people will be practising a given sequence together. There are

numerous sequences advocated by the various different schools of Tai Chi,

passed down partly through the written word but mostly from Shifu (master) to

pupil. Some pupils then go on to becomes Shifus themselves and so it goes on

down through the years. Some masters even claim direct lines of descent, Shifu

to pupil, going back to the origins of Tai Chi itself.

There was a brief stage though, a decade or so in length,

when this sequence was very nearly broken and Tai Chi itself nearly became

merely an historical artefact rather than the living, growing cultural

phenomenon that it is today. This period was known as the 'Cultural Revolution'

and lasted from the mid sixties to the early seventies. Tai Chi was deemed by

the advocates of the Cultural Revolution to be reactionary and hence unworthy

of being followed by the Chinese populace. Practitioners were persecuted, some

even ended up in prison where not a few were unable to survive the extremely

harsh conditions imposed by the Chinese penal system of the time.

The Shifu of the person who teaches my friend is now a

venerable old man in his mid eighties, though it is difficult to tell from his

upright posture and the smooth and beautifully co-ordinated movements he makes

when he goes through a sequence. He lives in a large city in Sichuan province

which today is enjoying the benefits of a booming economy and a good standard

of living. It was not always thus though. Back in the sixties it was caught up

in the storm that was the Cultural Revolution and he himself came very close to

being imprisoned for his 'counter-revolutionary' activities.

He had to promise to not only stop only teaching Tai Chi

but to give up personally practising it himself. He found the latter promise

impossible to keep though. At this stage of his life he had already been

practising for many years and he was aware of the enormous benefits that such

continuous practise had bought him. He chose to continue but to be very quiet

about it. Sometimes he would practise in the dead of night at home when he

thought all his neighbours must be asleep. Sometimes he slunk off in the middle

of the night and practised in the local forest or in the cemetery. On one of

these sojourns to the graveyard he even came across the man who had been his

Shifu beforehand, the tow men practising an exercise known as 'push hands' together.

The Cultural Revolution was, in one sense, an event unique

to China but in another just a repetition of a sequence that has gone on for

centuries. The leaders of revolutions, and generally those who seize power

through violence, seem to suffer an enormous fear, a paranoia if you will, that

that power so taken will be taken away from them, and maybe in a similarly

violent way to which they had acquired it in the first place. In reaction to

this there is often an attempt to almost start history anew, as if they could

re-invent the whole of society in exactly the way they wish it to be, usually

with themselves held up as the supreme leader. Even calenders may be reset to

year zero (as was the case with French Revolution and with the Khmer Rouge).

Perhaps this could be thought of as the ultimate in control-freakery.

The French Revolution could be thought of as one example,

although in that particular case the violent and irrational forces unleashed by the revolutionaries rebounded on themselves (Robespiere being one of many who suffered

this particular fate). Pol Pot's

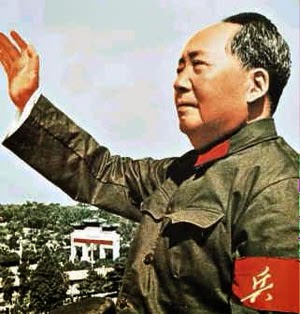

Cambodia would be another, perhaps even more extreme case. Mao's China a third,

although the cultural revolution came some years after the original revolution

when Mao could see that his grip on power was waning following the disaster of his economic policy known, somewhat ironically it would seem now, as 'The Great Leap Forward' (perhaps more aptly termed 'The Great Fall

Backwards!'). Mao is often called 'The Great Helmsman' in China and that would

be true, if you think that a great helmsman is someone who steers his ship onto

the rocks! He is often treated almost like a deity, the disaster of his policies

ignored in a strangely enduring cult of personality. The man actually

responsible for much of the economic and social progress in China today, Deng

Xiaoping, is barely ever mentioned.

Indeed, it was Deng Xiaoping who as leader deemed that

there was, after all, nothing wrong with Tai Chi. After years of being fearful

to practise their art, people started to emerge into the light once again and

Tai Chi once more resumed the cultural role that it had played in China over

many hundreds of years. Unfortunately, it was too late for some. The Shifu of

the man who practised in the cemetery was apprehended one day soon after and,

after a perfunctory trial, sent to a labour camp. He never returned. Now his pupil is a great Shifu in his own right and held in great respect across China.

How times change...

My friend is not only a great devotee of these arts but is, in truth, a very skilful practitioner too. I, for my part, am a mere dilettante as far

as these things go. I must admit though, despite its sometimes painfully masochistic

quality, there is something very energising about Pai Da. Fifteen minutes of

such exercises leaves one literally buzzing with energy in a way that

conventional exercise never does. One may be feeling a little tired

or jaded at the start but by the time the short session is finished you feel like you could

take on the planet! I am not sure that I buy into ideas of Chi as a

universal energy source but... I have to admit the affects of the practices.

They are very direct and very difficult to ignore. Also, when one sees men in

their mid eighties prancing around like teenagers it does tend to give one

pause for thought. I am not sure how or why it works, but it is clear that

something very significant is triggered by these strange but somehow very effective forms of exercise.

Back in the café I finish off my second bowl of dou nai by

picking it up and sipping directly from the bowl. The longer I am in China the

more I seem to be picking up the local habits. It may be a good idea to be a

little conscious of this if and when I eventually return to the West, slurping

from bowls is generally not 'de rigeur' in those parts. I am also sorely tempted

to have another portion of chang fen, a very pleasant and very filling dish

that is not dissimilar to lasagne, but without the cheese. At the princely sum

of 3.5 Yuan (35p or 50 cents) it is hard to resist but I growing increasingly

aware of my ever increasing waistline – it has been doing so steadily since I arrived in China, despite the amount

of exercise I have done. Better to resist for now methinks and leave it for

another day.

The sun is out, it is around 20C and I sit here in shirt

sleeves watching the world go by enjoying the last of my drink and another

completed blog. Life could be a lot worse...